skip to main |

skip to sidebar

The folks at Harper Voyager UK just released this cool book trailer for Peter V. Brett's The Daylight War (Canada, USA, Europe).

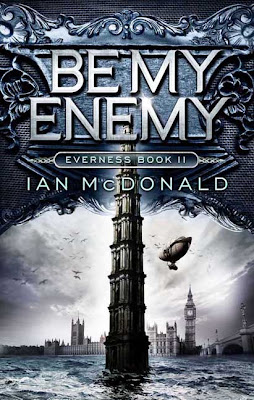

If you've been following this blog for a while, you are aware that I love Ian McDonald. To this day, River of Gods, Brasyl, and The Dervish House continue to rank among my favorite science fiction reads of all time. Hence, you can imagine my disappointment when it was announced that McDonald's next project would be aimed at the YA market.

Having said that, even though I gave Planesrunner a shot with a certain measure of reticence, the author's first YA work impressed me. Although the plot did not show as much depth and the storylines were not as multilayered and convoluted as is usually his wont, I found McDonald's Planesrunner to be an intelligent, entertaining, and fast-paced novel.

The sequel, Be My enemy, follows in the same vein. The book doesn't move the plot forward as much as the first installment did, but this second volume is another fun and entertaining novel which contains all the key ingredients that made Planesrunner such a good read!

Here's the blurb:

Everett Singh has escaped with the Infundibulum from the clutches of Charlotte Villiers and the Order, but at a terrible price. His father is missing, banished to one of the billions of parallel universes of the Panoply of All World, and Everett and the crew of the airship Everness have taken a wild, random Heisenberg Jump to a random parallel plane. Everett is smart and resourceful, and, from a frozen earth far beyond the Plenitude, he plans to rescue his family. But the villainous Charlotte Villiers is one step ahead of him.

The action traverses the frozen wastes of iceball earth; to Earth 4 (like ours, except that the alien Thryn Sentiency occupied the moon in 1964); to the dead London of the forbidden plane of Earth 1, where the emnants of humanity battle a terrifying nanotechnology run wild—and Everett faces terrible choices of morality and power. But Everett has the love and support of Sen, Captain Anastasia Sixsmyth, and the rest of the crew of Everness—as he learns that the deadliest enemy isn't the Order or the world-devouring nanotech Nahn—it's yourself.

It's no secret that the multiverse theory is an old science fiction trope. Some would say that parallel universes and parallel Earths have been done ad nauseam. That may be, but I found McDonald's approach, with such concepts as the Plenitude of Known Worlds and the Heisenberg Gates, to be relatively fresh. In Be My Enemy, the author explores a number of other realities. Given how Planesrunner ended, this second volume begins in a world trapped in ice and snow. In addition, the narrative takes readers to Earth 4, a world almost identical to our own but for mankind making contact with aliens in 1964. We also visit Earth 1, a forbidden plane of existence under quarantine where humanity has been brought on the brink of extinction by nanotechnology.

Though very fluid, McDonald's prose is evocative and every world and locale comes alive as you read along. I particularly enjoyed how arresting the imagery created by the author for the almost-dead world of Earth 1 turned out to be. The scenes taking place aboard the Everness are also special.

The coolest aspect of Be My Enemy remains McDonald's use of Everett's double from another plane of existence. That was absolutely brilliant and it opened up so many possibilities. Another Everett who knows virtually everything his counterpart does, but enhanced with alien Thryn technology, this teenager is forced by Charlotte Villiers to go after Everett Singh and the secrets he carries. But what the Plenipotentiaries failed to grasp is that this other Everett also has plans of his own.

Once more, the characterization is top notch. McDonald came up with an endearing and disparate cast of protagonists for Planesrunner and most of them are back in this second installment. Everett Singh must share the spotlight with his double from Earth 4 and there is a nice balance between the two POVs. The crew of the airship Everness makes for a compelling supporting cast, and it was a pleasure to see Captain Anastasia Sixsmyth, the mysterious Sen, the God-fearing Mr.Sharkey, and the grumbling Mchynlyth again.

As was the case with its predecessor, the pace is fast and crisp throughout Be My Enemy. So much so that you go through this slim (269 pages) book in no time. As I mentioned earlier, this volume focuses more on the confrontation between Everett Singh and Everett M than anything else, which means that the storylines don't progress as much as I would have thought. Still, the way the author brought Be My Enemy to a close opens the door for plenty of awesome things to come, in a number of different realities. Lou Anders told me that volume 3 should, if all goes well, see the light in the winter of 2014.

All in all, Be My Enemy may not be akin to the mind-blowing science fiction yarns Ian McDonald is renowned for. And yet, like Planesrunner, it's a fun, entertaining, more and more complex work featuring an engaging cast of characters. If like me, you have a bias against YA books, McDonald's Everness series should win you over. Writing for a younger audience imbues McDonald's writing with a certain exuberance that I found intoxicating.

Give these books a shot! Planesrunner and Be My Enemy won't disappoint!

The final verdict: 7.75/10

For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe

You can now download John Scalzi's third episode in The Human Division series, We Only Need the Heads, for 0.99$ here.

Here's the blurb:

The third episode of The Human Division, John Scalzi's new thirteen-episode novel in the world of his bestselling Old Man's War. Beginning on January 15, 2013, a new episode of The Human Division will appear in e-book form every Tuesday.

CDF Lieutenant Harry Wilson has been loaned out to a CDF platoon tasked with secretly removing an unauthorized colony of humans on an alien world. Colonial Ambassador Abumwe has been ordered to participate in final negotiations with an alien race the Union hopes to make allies. Wilson and Abumwe’s missions are fated to cross—and in doing so, place both missions at risk of failure.

At the publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied.

Bantam Books have re-issued George R. R. Martin's Tuf Voyaging in trade paperback format and I'm giving away a copy to one lucky winner! For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe.

Here's the blurb:

Long before A Game of Thrones became an international phenomenon, #1 New York Times bestselling author George R. R. Martin had taken his loyal readers across the cosmos. Now back in print after almost ten years, Tuf Voyaging is the story of quirky and endearing Haviland Tuf, an unlikely hero just trying to do right by the galaxy, one planet at a time.

Haviland Tuf is an honest space-trader who likes cats. So how is it that, in competition with the worst villains the universe has to offer, he’s become the proud owner of a seedship, the last remnant of Earth’s legendary Ecological Engineering Corps? Never mind; just be thankful that the most powerful weapon in human space is in good hands—hands which now have the godlike ability to control the genetic material of thousands of outlandish creatures.

Armed with this unique equipment, Tuf is set to tackle the problems that human settlers have created in colonizing far-flung worlds: hosts of hostile monsters, a population hooked on procreation, a dictator who unleashes plagues to get his own way . . . and in every case, the only thing that stands between the colonists and disaster is Tuf’s ingenuity—and his reputation as a man of integrity in a universe of rogues.

The rules are the same as usual. You need to send an email at reviews@(no-spam)gryphonwood.net with the header "TUF." Remember to remove the "no spam" thingy.

Second, your email must contain your full mailing address (that's snail mail!), otherwise your message will be deleted.

Lastly, multiple entries will disqualify whoever sends them. And please include your screen name and the message boards that you frequent using it, if you do hang out on a particular MB.

Good luck to all the participants!

But we still know how to have a good time!! ;-)

Indie authors. . .

As a huge fan of Robin Hobb and her Six Duchies novels, I was thrilled when it was announced that she was writing a novella which would focus on the Farseer line's magical power. With The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince, the author would finally reveal how the Farseer family acquired their mysterious powers. I was quite intrigued, to say the least!

Here's the blurb:

One of the darkest legends in the Realm of the Elderlings recounts the tale of the so-called Piebald Prince, a Witted pretender to the throne unseated by the actions of brave nobles so that the Farseer line could continue untainted. Now the truth behind the story is revealed through the account of Felicity, a low-born companion of the Princess Caution at Buckkeep.

With Felicity by her side, Caution grows into a headstrong Queen-in-Waiting. But when Caution gives birth to a bastard son who shares the piebald markings of his father’s horse, Felicity is the one who raises him. And as the prince comes to power, political intrigue sparks dangerous whispers about the Wit that will change the kingdom forever…

Internationally-bestselling, critically-acclaimed author Robin Hobb takes readers deep into the history behind the Farseer series in this exclusive, new novella, “The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince.” In her trademark style, Hobb offers a revealing exploration of a family secret still reverberating generations later when assassin FitzChivalry Farseer comes onto the scene. Fans will not want to miss these tantalizing new insights into a much-beloved world and its unforgettable characters.

The novella is split into two parts, "The Willful Princess" and "The Piebald Prince." The first one focuses on Princess Caution Farseer, willful daughter of King Virile and Queen Capable. It chronicles the events of her life, from her name-sealing day until the day she gave birth to her only child. From the beginning, Caution is a spoiled brat who'll become an annoying teenager, and then a capricious Queen-in-Waiting.

The tale is told by Felicity, daughter of Princess Caution's wet-nurse. Although low-born, Felicity will become Caution's best friend, confidante, and lover. Trouble is, Felicity isn't a very interesting or even likeable POV protagonist. And since the entire novella unfolds through her eyes, that creates a problem. I understand that for the secrets to go down through the subsequent Farseer generations, it needed to be recorded by a third party. Hence, Felicity and Redbird's importance cannot be put into question. It's just that Felicity isn't an engaging narrator. And given how critical and fascinating the truth behind the Farseer's mysterious magical powers will be in the two series featuring the beloved character FitzChivalry, I believe the tale would have been better had it featured POVs by Princess Caution, Lostler, Lord Canny, Lady Wiffen, and King Charger.

I feel it would have given more depth to the story. As things stand, with everything being recounted by Felicity, the novella lacks the usual emotional punch that characterize basically all of Robin Hobb's tales.

Beyond the secrets behind the Farseer line's mystical powers, I enjoyed how The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince also elaborated on why the Wit became so feared and Witted People became persecuted all over the Six Duchies.

Although Hobb's storylines are as absorbing as is habitually her wont, I found that Felicity's narrative could be a bit off-putting at times. The pace can drag a bit in certain portions of the first part. Yet the rhythm is perfect in "The Piebald Prince."

Regardless of its shortcomings, I found The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince to be a worthy addition to the Six Duchies' canon. Can't wait to read another novel/series featuring FitzChavalry again!!

The final verdict: 7.25/10

For more info about this title, check out the Subterranean Press website.

Thanks to the folks at Del Rey, here's an excerpt from Robert V. S. Redick's The Night of the Swarm. For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe.

Here's the blurb:

Robert V. S. Redick brings his acclaimed fantasy series The Chathrand Voyage to a triumphant close that merits comparison to the work of such masters as George R. R. Martin, Philip Pullman, and J.R.R. Tolkien himself. The evil sorcerer Arunis is dead, yet the danger has not ended. For as he fell, beheaded by the young warrior-woman Thasha Isiq, Arunis summoned the Swarm of Night, a demonic entity that feasts on death and grows like a plague. If the Swarm is not destroyed, the world of Alifros will become a vast graveyard. Now Thasha and her comrades—the tarboy Pazel Pathkendle and the mysterious wizard Ramachni—begin a quest that seems all but impossible. Yet there is hope: One person has the power to stand against the Swarm: the great mage Erithusmé. Long thought dead, Erithusmé lives, buried deep in Thasha’s soul. But for the mage to live again, Thasha Isiq may have to die.

Enjoy!

-----------------------

Author’s Note: the setting of this chapter is the ancient sailing ship Chathrand, Captain Nilus Rose commanding, as it flees the hostile waters of the empire of Bali Adro. There are quite a few actors on stage (on deck) but I think readers will be able to follow the dynamics of the scene without knowing all the personalities involved.

From the Final Journal of G. Starling Fiffengurt, Quartermaster

Wednesday, 20 Halar 942. The wolves have finally pounced.

As I write this, I feel how lucky we are to be alive. Whether luck & life will still be with us much longer is uncertain. For now all credit goes to Captain Rose. People change; ships grow faster, arms more diabolical. But nothing beats a seasoned skipper, no matter his moods or eccentricities.

Five bells. Lunch still heavy in my stomach. A shout from the crow’s nest: Ship dead astern! I happened to be right there at the wheel with Elkstem, and we rushed to the spankermast speaking-tube to hear the man properly.

“She was hid by the island, it’s not my fault!” he shouts. That told us next to nothing: there were islands all about us: great and small, settled and unsettled (though with each day north we saw fewer signs of habitation), sandy and stony, lush and bone-dry. We’d been winding among them for a week.

“A monster of a boat!” the lookout’s shouting. “Ugly, huge! She’s five times our measure if she’s a yard.”

“Five times our blary length?” cries the sailmaster. “Gather your wits, man, that’s impossible! Distance! Heading!”

“Maybe longer, Mr. Elkstem! I can’t be sure; she’s forty miles astern. And Rin slay me if she don’t have a halo of fire above her. Devil-fire, I mean! Something foul beyond foul.”

“What heading is she on, damn you?” I bellow.

“East, Mr. Fiffengurt, or east-by-southeast. They’re under full sail, sir, and—”

Silence. We both scream at the poor lad, and then he answers shrilly: “Correction, correction! Vessel tacking northward! They’ve spied us!”

Not just spied, but fingered us for dinner, it appeared. I blew the whistle; the lieutenants started bellowing like hounds; in seconds we were preparing for war.

From the hatches men spilled like ants, the dlömu answering the call as quickly as the humans, if not more so. Mr. Leef finally brought me a telescope. I raised it, but shut my eyes before I looked. No fear, no fear, the lads’ eyes are upon you.

The vessel was a horror. It was a Plazic invention to be sure, one of the foul things sustained by the magic the dlömu had drawn from the bones of the lizard-demons called eguar. Prince Olik had told us a little, and the dlömic sailors a little more. Eguar-magic was the power behind the Bali Adro throne, & its doom. It had made her armies invincible—and made their commanders depraved and self-destroying. It is a frightful state of affairs, and one that reminds me uncomfortably of our own dear Empire across the sea.

We’d seen monster-vessels before, in the terrible Armada that passed so close to us just after we reached the Southern main. But this was something else altogether. Impossibly large and shapeless, it was like a giant, shabby fortress or cluster of warehouses that had somehow gone to sea. How did it move? There were sails, but they were preposterous: ribbed things that jutted out like the fins of a spiny rockfish. It should have been dead in the water, but the blue gap between it & the island was growing. It was under way.

Captain Rose bounded up the Silver Stair. Without a glance at me he climbed the quarterdeck ladder, and kept going to the mizzen yard, where he trained his own scope on the vessel. He held still a long time (what’s a long time when your heart’s in your throat?) as Elkstem and I gazed up at him. When he turned to us, his look was sober and direct.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “you are distinguished seamen: use your skills. This foe we cannot fight. We must elude it until nightfall or we shall lose the Chathrand.”

The captain’s rages are frightful, but his compliments simply terrify: he saves them for the worst of moments. He hung there, face unreadable within that red beard, one elbow hitched around a backstay. He examined the skies: blue above us, thick clouds to windward. Islands on all sides, of course. Rose looked over each of them in turn.

His eyes narrowed suddenly. He pointed at a dark, mountainous island, some forty miles off the starboard bow. “That one. What is it called?”

Elkstem told him that it was Phyreis, one of the last charted islands in the Wilderness. “And a big one, Captain. Half the size of Bramian, maybe,” he said.

“It appears to sharpen to a point.”

“The chart attests to it, sir: a long southwest headland.”

Rose nodded. “Listen well, then. We must be fifteen miles off that point at nightfall. That will be at seven bells plus twenty minutes. Until then we are to stay as far as possible ahead of the enemy, without ever allowing him to cut us off from Phyreis. Is that perfectly clear?”

“By nightfall—” I began.

“Fiffengurt.” He cut me off, suddenly wrathful. “You have just disgraced your very uniform. Did I say by nightfall? No, Quartermaster: my command was at nightfall. Earlier is unacceptable, later equally so. If these orders are beyond your comprehension I will appoint someone fit to carry them out.”

“Oppo, sir,” I said hastily. “At nightfall, fifteen miles off the point.”

Rose nodded, his eyes still on me. “The precise course I leave to your combined discretion. The canvas likewise. That is all.”

And that was all. Rose sent word that he required Tarsel the blacksmith and six carpenters to join him on the upper gun deck, and lumbered off toward the No. 3 hatch, shouting at his attendant ghosts: “Clear out, stand aside. Don’t touch me, you stinking shade! I know what a barometer is. Damn you all, stop talking and let me think!”

Elkstem and I put the men to spreading all the canvas we could think of; the winds were that sluggish. I even sent a team down to the orlop, digging for the moonrakers that hadn’t been touched since the Straits of Simja. Then we dived into our assignment: plotting, calculating, fighting over the math. It is no easy job to ensure that one arrives at a distant spot neither early nor late, above all when one must seem to be fleeing. And to make matters worse, we were fleeing. There was the open question of just how fast that unnatural behemoth could move. One thing was clear, though: far more than wind propelled it over the seas.

The Chathrand, however, remains a beauty of a sailing ship. Despite the torpid day she was making thirteen knots by the time we ran out the studding sails. I was proud of her: she’d weathered a great deal and come through. But the Behemoth was still gaining. As it crept nearer I studied it again. A monstrosity. Great furnaces along her length, belching fire and soot. Black towers and catapults & cannon in unimaginable numbers; giving the whole thing the look of a sick, warty animal. Hundreds, maybe a few thousand men, crowded onto her topdeck. What possible use for so many?

“Traitor!”

I ducked with a curse. It was Ott’s falcon, Niriviel. The bird screamed low over my head, shrieking, & alighted on the roof of the wheelhouse. It was the fourth time this week.

“Bird!” I sputtered. “I swear on the Blessed Tree, if you ever come at me like that again—”

“My master orders me to announce my mission!” it shrilled. “I go on reconnaissance. My master requires you to inform me of the distance between the ships.”

“The distance? About thirty miles, currently, but see here—”

“I hate you. You’re a mutineer, a friend of Pathkendle and the Isiq girl. Why aren’t you in chains?”

“Captain Rose finds me more useful here than in the brig. Now listen, bird, stay well above that ship, we don’t know what sort of weapons they—”

“Some enemies sail over the horizon, coveting our land and gold,” cried the falcon, “but worse are the sons of Arqual whom the Emperor has showered with love, and who do not love him in return.”

“Showered with love! Oh flap off, you blary simpleton!”

Niriviel stepped from the roof, beat his wings, and shot away southward. The bird’s abuses make me livid, but I can’t manage to hate him for long. The poor beast was lost for a month after the Red Storm, and Ott seemed almost human in the way he nursed him back to strength—feeding him bite after bite of raw, fresh chicken, along with ample fibs about the greatness of Arqual and the vileness of her enemies. I think often of Hercól’s assessment: “Niriviel is a child soldier: trained in fanaticism, more a believer than those who taught him to believe.” In other words, a simpleton. But a useful one: he might well come back with knowledge that would save the ship.

We went on tacking north. Clouds rolled in, their gray bellies heavy with rain, although for now it refused to fall. The wind freshened as well: soon we were at fifteen knots. Elkstem and I watched the Behemoth, and after a bit we exchanged a smile. The gap between us was no longer shrinking: indeed it was, ever so slightly, growing. The Behemoth was falling behind.

“Give me an honest wind over magecraft any day of the week,” said Elkstem. In a voice meant just for me, he added: “Tree of Heaven, Graff, I thought we were dead.”

Marila, bless her, brought tea and biscuits to the quarterdeck. Her own belly is showing now, a little fruit bowl tucked under her shirt. In her arms was Felthrup, squirming with impatience to move: it was his first venture beyond the stateroom since the attempt on his life. As soon as his feet touched the boards he raced the length of the quarterdeck & back again, then dashed excitedly about our heels.

“Prince Olik spoke the truth!” he squeaked. “That ship is a mutant thing, a mishmash held together by spells alone! The Plazic forces are in decline. The power they seized has devoured them like termites from within, and turned them senseless and savage. But not for long! Olik said they were melting, those Plazic weapons, and that Bali Adro cannot make any more.”

“Not without the bones of them crocodile-demons, is it?” said Elkstem.

“Very good, Mr. Elkstem! Not without the bones of the eguar—and they have no more, for they have plundered the last of the eguar Grave-Pits. They are drunkards, taking the last sips from the bottle of power, and reeling already from withdrawal.”

“I believe you, Ratty,” I said, “but it’s no real comfort at the moment. Their last sips of power may blary well kill us.”

“Do you really think so?”

As if the Behemoth wished greatly to convince one little rat, something massive boomed on her deck. I snapped my scope up, hoping that one of those furnaces had exploded and torn her apart. No luck: it was rather the opening of a tremendous metal door. At first I couldn’t see what lay beyond that door. But after several minutes I made out what looked like a bowsprit, and then a battery of guns. Something was detaching itself from the Behemoth and gliding out upon the waves.

“Graff,” Elkstem murmured to me, gazing through his more powerful scope. “Do you know what that is? A sailing vessel, that’s what. I mean a regular ship like our own. And blast me if she ain’t got four masts!”

“You must be wrong,” I said. “The monster can’t be that big.”

But it was not long before I saw for myself that it was true. My hands went icy. “That colossus,” I said, “it’s is a naval base. A movable naval base. We’re being pursued by a mucking shipyard.”

“It’s the daughter-ship that worries me,” said Elkstem.

The daughter-ship, the four-master, was narrow and sleek. She might have been a pretty vessel, once, but now her lines were ruined by great sheets of armor welded to her hull. All the same she would be faster than the Behemoth.

Her crew began spreading canvas. Elkstem growled. “They’re clever bastards. That four-master will catch us, sooner or later, unless the wind decides to double. We could outfight her, maybe—but so what? All she needs to do is nip our heels, hobble us with a few shots to the rigging. Once we’re slowed, the monster can catch up and finish us.”

“Mr. Fiffengurt,” said Marila, who had taken my telescope, “what if they don’t catch us by nightfall?”

“Why, then our chances improve,” I said, “so long as we keep the lights out on the Chathrand. They could very well lose us in the dark. Of course we won’t know until morning. We could even wake up and find ’em right on top of us.”

Marila started. “Something’s happening on the big ship,” she said. “They’re moving something closer to the rail.”

Before I could take back the telescope there came a new explosion. From the deck of the Behemoth a thing of flame was blasting skyward on a rooster-tail of orange sparks. A rocket, or a burning cannon-shot. Its banshee howl caught up with us, but the shot itself was not approaching, only climbing higher & higher. Suddenly it burst. Five lesser fireballs spread from the core like the spokes of a wheel: beautiful, terrible.

“Maybe they’re trying to be friendly?” said a lad at the mizzen.

Then, in unison, the fireballs swerved, came together again, and began to scream across the water in our direction.

Terror gripped us all. I bolted from the wheelhouse, shouting: “Fire stations! Third and fourth watch to the pumps! Hoses to the topdeck! Run, lads, run to save the ship!”

Marila had scooped up Felthrup and was racing for the ladderway. The fireballs had twenty miles to cover, and from the look of it they would do so in the next three minutes. But what sort of projectile could change course in midair?

“Drop the mains, drop the topsails!” Elkstem was shouting. And that of course should have been my first command: those ten giant canvases made for a target twice the size of the hull, and they would burn far more easily too. Someone (Rose?) at the bow had given the same order; already the sails were slinking down the masts.

By the grace of Rin we got the big sails down, and even furled the jibs & topgallants. All in about two minutes flat. I was by now down on deck and heading for the mainmast. I saw the first fire-team near the Holy Stair, wrestling with a hose that was already gushing salt water. But there were none close to me. I leaned over the tonnage hatch, screaming: “Where’s your team, Tanner, you boil-arsed dog?” When I turned the men on deck were staring skyward. I whirled. A fireball was plummeting straight for us.

“Cover! Take cover!”

Everyone ran. I threw myself behind the No. 4 hatch coaming. But I had to look—my ship was about to be massacred—so at the last second I raised my eyes.

What I saw was a nightmare from the Pits. The fireball was no shot, no chunk of phosphorous or glob of burning tar. It was a creature: vaguely wasp-like, its great segmented body blazing like a torch, and it struck the deck and splattered flame in all directions like a dog shaking water from its fur.

I dropped, horrified. My hair caught fire but I snuffed it quick. A blizzard of sparks blew past me; without the hatch I’d have been roasted on the spot. When I looked up and down the length of the ship I thought our doom had come, for all I saw was fire. Get up, I thought, move and fight while you can! There were screams from fifty men, a gigantic howling and thumping from the creature itself. I don’t know how I made myself stand and face the thing, but I did.

Heat struck me like a blow. The creature had smashed halfway through the deck and was lodged there, dying. It had made a suicide plunge, and when it struck its body had burst open like a melon. As it writhed and heaved flame gushed from it like blood. Where was the rain? Where was our mucking skipper? I looked the ship up and down, and thought we were finished, doomed: for all I saw was flame. Right in front of me a man caught fire: who he was I could not tell. He was running, screaming, & the flames wrapped him like a flag.

Then a mighty spray of water hit the man, knocking him clean off his feet. Rose and five marines were there behind me with a fire hose. They had wrestled it up the No. 4 and were blasting the poor wretch with all the force sixty men at the chain-pumps could deliver. Thank Rin, it worked: he was doused, and two mates seized him and bore him away. Then Rose turned the spray around to the creature. It screamed and twitched and vomited fire, but it could not flee the blast. Very soon it was sputtering out.

Fire still blazed everywhere, though. At least four of the five creatures had exploded in like fashion. One had torn through the standing rigging, causing the entire mizzenmast to sway. The battle nets were burning, the port skiff was burning, halyards were falling to the deck in flaming coils. Beside me, Jervik Lank threw a younger tarboy into the lifesaving spray, and I swear I heard the hiss as his clothes were extinguished. At the forecastle, Lady Oggosk opened her door, shrieked aghast and slammed it again.

Suddenly Rose exploded: “Mizzenmast! Belay hauling! Belay! Damnation! BELAY!”

The men aloft could not hear him. Rose left the Marines and ran straight through the fire, then swung out onto the mainmast shrouds, over the water, waving his hat and screaming for all he was worth. I saw the danger: high on the mizzenmast, the brave lads were trying to save their mainsail by lifting it clear of the smoldering deck. But a line was fouled in the sail—a burning line. They couldn’t see it for the smoke, but they were about to spread the fire to the upper sails.

Captain Rose got their attention at last, and you may be sure they belayed. I looked around me, and by Rin! there was hope. All the creatures had been snuffed, the hoses were still blasting, and save for the mizzenmast the rigging was remarkably intact.

“Two of them mucking animals burned up ’fore they could reach us,” said Jervik Lank, popping up beside me again. “And when their fire died they just fell into the sea.”

So we were at the edge of their range. That answered one question: maybe they preferred to take us alive, but failing that they didn’t want us to escape. They’d waited as long as they dared to hurl those obscene fire-insects at us, then let loose before we could slip away.

The hose-teams went on blasting, and it began to look as though we’d won a round. The Chathrand had lost her jibsail, one minor lifeboat, some rigging about her stern. It was an unholy mess, and work for the carpenters for a fortnight. But the daughter-ship was still miles off, and the day was ending, and they hadn’t sunk us yet. Best of all there was no sign of another volley like the first.

“Captain Rose, you’ve done it—Aya Rin! Captain!”

His left arm was on fire. “Nothing, pah!” he said, calmly stripping off his coat. But the Marines were taking no chances. They still had hold of that writhing dragon of a fire hose, and with a cry they swung around and aimed it at their burning captain—and blew him right off the shrouds and into the sea.

----------------------------

Excerpted from The Night of the Swarm by Robert V. S. Redick. Copyright © 2013 by Robert V. S. Redick. Excerpted by permission of Del Rey, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A final update as I finished Robert Jordan and Brandon Sanderson's A Memory of Light (Canada, USA, Europe) yesterday. This was the Facebook update I posted a few minutes after reaching the end:

Just finished A MEMORY OF LIGHT. . . Fuck. . . Nowhere near as bad as the Dune travesty, thankfully. But close. . . Sanderson, though it wasn't perfect, did a relatively good job with THE GATHERING STORM and THE TOWERS OF MIDNIGHT. How he could mess it up so badly at the end, I'll never know. . . =( Waited 22 years for this. . . Biggest literary disappointment of my life. . . Would have preferred the notes and the outline to what we ended up getting. . . =( Bad. . .

A Memory of Light is by far the weakest installment in the series, weaker even than Crossroads of Twilight. Man, I so wanted to love this book. How can WoT end on such a crappy note???

Expect my review in the near future. . . =(

You can now download John Scalzi's Walk the Plank, the second episode in The Human Division, for only 0.99$ here.

Here's the blurb:

The second episode of The Human Division, John Scalzi's new thirteen-episode novel in the world of his bestselling Old Man's War. Beginning on January 15, 2013, a new episode of The Human Division will appear in e-book form every Tuesday.

Wildcat colonies are illegal, unauthorized and secret—so when an injured stranger shows up at the wildcat colony New Seattle, the colony leaders are understandably suspicious of who he is and what he represents. His story of how he’s come to their colony is shocking, surprising, and might have bigger consequences than anyone could have expected.

At the publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied.

I have three copies of L. E. Modesitt, Jr.'s Imager's Battalion up for grabs, compliments of the folks at Tor Books. For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe.

Here's the blurb:

The sequel to the New York Times bestselling Princeps follows magical hero Quaeryt as he leads history's first Imager fighting force into war. Given the rank of subcommander by his wife's brother, Lord Bhayar, the ruler of Telaryn, Quaeryt joins an invading army into the hostile land of Bovaria, in retaliation for Bovaria's attempted annexation of Telaryn. But Quaeryt has his own agenda in doing Bhayar's bidding: to legitimize Imagers in the hearts and minds of all men, by demonstrating their value as heroes as he leads his battalion into one costly battle after another.

Making matters worse, court intrigues pursue Quaeryt even to the front lines of the conflict, as the Imager's enemies continue to plot against him.

You can read an extract from the novel here.

The rules are the same as usual. You need to send an email at reviews@(no-spam)gryphonwood.net with the header "BATTALION." Remember to remove the "no spam" thingy.

Second, your email must contain your full mailing address (that's snail mail!), otherwise your message will be deleted.

Lastly, multiple entries will disqualify whoever sends them. And please include your screen name and the message boards that you frequent using it, if you do hang out on a particular MB.

Good luck to all the participants!

You can now download Timothy Zahn's Star Wars novella Winner Lose All for 1.99$ here.

Here's the blurb:

Timothy Zahn’s upcoming novel Scoundrels, starring Han Solo, Chewbacca, and Lando Calrissian, returns to the excitement of the classic Star Wars films. In this thrilling prequel eBook novella, Winner Lose All, Lando and a pair of unlikely allies find themselves involved in a dangerous game. Fortunately, Lando can survive against the odds—a skill that he will need in spades.

Lando Calrissian’s no stranger to card tournaments, but this one has a truly electrifying atmosphere. That’s because the prize is a rare sculpture worth a whopping fifty million credits. If Lando’s not careful, he’s going to go bust, especially after meeting identical twins Bink and Tavia Kitik, master thieves who have reason to believe that the sculpture is a fake. The Kitiks are beautiful, dangerous, and determined to set things right—and they’ve convinced Lando to help them expose the scam. But what they’re up against is no simple double cross, nor even a twisted triple cross. It is a full-blown power play of colossal proportions. For an unseen mastermind holds all the cards and has a fail-proof solution for every problem: murder.

Thanks to the generosity of the author, I have an Advance Reading Copy of Peter V. Brett's The Daylight War for you to win! Even better, Brett will personalize the book for you! For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe.

Here's the blurb:

With The Warded Man and The Desert Spear, Peter V. Brett surged to the front rank of contemporary fantasy, standing alongside giants in the field like George R. R. Martin, Robert Jordan, and Terry Brooks. The Daylight War, the eagerly anticipated third volume in Brett’s internationally bestselling Demon Cycle, continues the epic tale of humanity’s last stand against an army of demons that rise each night to prey on mankind.

On the night of the new moon, the demons rise in force, seeking the deaths of two men both of whom have the potential to become the fabled Deliverer, the man prophesied to reunite the scattered remnants of humanity in a final push to destroy the demon corelings once and for all.

Arlen Bales was once an ordinary man, but now he has become something more—the Warded Man, tattooed with eldritch wards so powerful they make him a match for any demon. Arlen denies he is the Deliverer at every turn, but the more he tries to be one with the common folk, the more fervently they believe. Many would follow him, but Arlen’s path threatens to lead him to a dark place he alone can travel to, and from which there may be no returning.

The only one with hope of keeping Arlen in the world of men, or joining him in his descent into the world of demons, is Renna Tanner, a fierce young woman in danger of losing herself to the power of demon magic.

Ahmann Jardir has forged the warlike desert tribes of Krasia into a demon-killing army and proclaimed himself Shar’Dama Ka, the Deliverer. He carries ancient weapons—a spear and a crown—that give credence to his claim, and already vast swaths of the green lands bow to his control.

But Jardir did not come to power on his own. His rise was engineered by his First Wife, Inevera, a cunning and powerful priestess whose formidable demon bone magic gives her the ability to glimpse the future. Inevera’s motives and past are shrouded in mystery, and even Jardir does not entirely trust her.

Once Arlen and Jardir were as close as brothers. Now they are the bitterest of rivals. As humanity’s enemies rise, the only two men capable of defeating them are divided against each other by the most deadly demons of all—those lurking in the human heart.

Our winner will also receive copies of the mass market paperback edition of both The Warded Man (Canada, USA, Europe) and The Desert Spear (Canada, USA, Europe), the first two volumes in the series.

The rules are the same as usual. You need to send an email at reviews@(no-spam)gryphonwood.net with the header "DAYLIGHT." Remember to remove the "no spam" thingy.

Second, your email must contain your full mailing address (that's snail mail!), otherwise your message will be deleted.

Lastly, multiple entries will disqualify whoever sends them. And please include your screen name and the message boards that you frequent using it, if you do hang out on a particular MB.

Good luck to all the participants!

Ace have just released a book trailer for Myke Cole's Shadow Ops series, which includes Shadow Ops: Control Point (Canada, USA, Europe) and Shadow Ops: Fortress Frontier (Canada, USA, Europe).

Highly recommended! =)

A true classic from New Order and one of the best songs from the 80s! =)

A new update as I go through Robert Jordan and Brandon Sanderson's A Memory of Light (Canada, USA, Europe). I've just reached the 700-page mark. I would have thought that this far along into the book, everything would be great. Sadly, that wasn't to be. . .

I've done a quick count as I watch the football game: Of the 700 pages I have read thus far, 389 pages are battle scenes. More than 50% of the book so far. But if you consider that most of what isn't about battle sequences has to do with either their preparation or their aftermath, I'd say that probably 80% of the novel only has to do with battles.

A Memory of Light remains one giant mess of POVs, and as we speak it is a veritable chore to go through. I'm skimming through parts of it now, for it's basically just one part of battles as seen through the eyes of yet another character. ALL FILLER, no killer. . . =(

Only the endgame can save this now, as Rand battles the Dark One. But in and of itself, A Memory of Light is pretty much a failure to launch. The proliferation of installments to cap off WoT was, as expected, one last attempt to cash in on a very popular series. A shame. . . =(

Myke Cole's Shadow Ops: Fortress Frontier is the sequel to what was the speculative fiction debut of 2012, Shadow Ops: Control Point (Canada, USA, Europe). I felt that the book was a fun, intelligent, action-packed, entertaining read with a generous dose of ass-kicking! It was fresh and unlike anything else I had ever read. But as fun to read as his debut turned out to be, the question remained: Could Cole possibly do it again?

The answer is a resounding yes! The author was smart enough to realize that there was no way he could use the same recipe and do it again. What made Shadow Ops: Control Point such an interesting read was the fact that it was more or less unique in the genre. And yet, in order to satisfy and keep readers for the rest of the series, Myke Cole would have to find a way to elevate his game and continue to surprise us and keep us on our toes. Which is exactly what he does throughout Shadow Ops: Fortress Frontier.

By building upon existing storylines from his debut and by adding layers to what is turning out to be a more complex tale than we were originally led to believe, the author came up with a terrific sequel that proves that Myke Cole is for real!

Here's the blurb:

The Great Reawakening did not come quietly. Across the country and in every nation, people began to develop terrifying powers—summoning storms, raising the dead, and setting everything they touch ablaze. Overnight the rules changed... but not for everyone.

Colonel Alan Bookbinder is an army bureaucrat whose worst war wound is a paper-cut. But after he develops magical powers, he is torn from everything he knows and thrown onto the front-lines.

Drafted into the Supernatural Operations Corps in a new and dangerous world, Bookbinder finds himself in command of Forward Operating Base Frontier—cut off, surrounded by monsters, and on the brink of being overrun.

Now, he must find the will to lead the people of FOB Frontier out of hell, even if the one hope of salvation lies in teaming up with the man whose own magical powers put the base in such grave danger in the first place—Oscar Britton, public enemy number one...

My main problem with Shadow Ops: Control Point was that I felt that Cole kept his cards too close to his chest. Indeed, he introduced cool concepts and fascinating ideas, but failed to elaborate on most of them. I wanted to discover a lot more about the Supernatural Operations Corps, the Source, the Goblins and other creatures, the act of Manifesting, as well as many other aspects of the worldbuilding. Well, I'm glad to report that the author opens up a bit more in this sequel, which adds more depth to the various story arcs.

Having served in the military allows Cole to imbue this series with a credibility regarding the realism of the use of magic and its ramifications up and down the chain of command. It gives this series its unique "flavor" and remains what sets it apart from everything else on the market.

Although he did grow on me in Cole's debut, I had doubts that do-gooder Oscar Britton could carry this series on his shoulders. Too empathic and introspective, Britton's emo side often clashed with his kick-ass personality. He means well, always, but the poor guy remains a bit clueless more often than not. Enter Colonel Alan Bookbinder, the main protagonist through whose eyes the bulk of the tale that is Shadow Ops: Fortress Frontier would unfold. A bureaucrat, a pencil-pusher who has never seen any action. A character readers are not supposed to root for. And yet, from the start, you can't help but love the guy. Thrust into an impossible situation without any combat experience, Bookbinder finds himself in command of hundreds of men and women cut off from the home plane. And somehow, he must find a way to save as many of them as humanly possible. An unlikely hero, Bookbinder will earn the loyalty of his troops and that of the reader. As a matter of course, familiar faces from the first volume return in this sequel, especially in the plotlines which revolve around Britton. As expected, both groups of characters join forces at some point. But there are quite a few surprises before that is allowed to happen.

What many considered Bookbinder's suicide mission allows Myke Cole to unveil more of the Source than we had seen thus far. So finally, we learn more about the landscape beyond FOB Frontier and the panoply of denizens found throughout the Source. In both Britton and Bookbinder's story arcs, we learn a lot more about magic. I also liked how the author brought politics into the fray, which will undoubtedly have repercussions in the final volume.

The pace is crisp throughout. As was the case with its predecessor, there is not a dull moment to be found within the pages of Shadow Ops: Fortress Frontier. Action-packed, smart, and entertaining, this second installment was a decidedly fun read! I'm definitely looking forward to the conclusion of the Shadow Ops series next year!

The final verdict: 8/10

For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe

You can now download The End of the World: Stories of the Apocalypse, an anthology edited by Martin H. Greenberg for only 0.99$ here.

Here's the blurb:

Before The Road, by Cormac McCarthy, brought apocalyptic fiction into the mainstream, there was science fiction. No longer relegated to the fringes of literature, this explosive collection of the world's best apocalyptic writers brings the inventors of alien invasions, devastating meteors, doomsday scenarios, and all-out nuclear war back to the bookstores with a bang.The best writers of the early 1900s were the first to flood New York with tidal waves, destroy Illinois with alien invaders, paralyze Washington with meteors, and lay waste to the Midwest with nuclear fallout. Now collected for the first time ever in one apocalyptic volume are those early doomsday writers and their contemporaries, including Neil Gaiman, George R. R. Martin, Lucius Shepard, Robert Sheckley, Norman Spinrad, Arthur C. Clarke, William F. Nolan, Poul Anderson, Fredric Brown, Lester del Rey, and more. Relive these childhood classics or discover them here for the first time. Each story details the eerie political, social, and environmental destruction of our world.

I know I've said I wanted to take my time and savour every moment as I go through Robert Jordan and Brandon Sanderson's A Memory of Light (Canada, USA, Europe). The death of my grandmother a little over a week ago and an acute case of gastroenteritis earlier this week have slowed me down quite a bit.

But I'm now about 500 pages into the book and it's been all filler and no killer so far. Hell, the first 400 pages or so were more or less boring. Things have been looking up a bit these last few chapters, but it's now obvious that Jordan's last WoT volume should never have been split into three installments.

A Memory of Light is a veritable mess of POVs that focus on everything but the really important stuff, or so it seems. I mean, do we truly need to witness every single skirmish taking place in Andor and the Borderlands??? So far, I'd say that about 70% of the book has focused on those battles.

And some of the most important scenes we have been waiting for for years and years are downright ridiculous. "He will bind the nine moons to serve him." Remember that prophecy about the Dragon Reborn? That scene was a fucking joke. . . =(

I know the grand finale will make or break this book. And in a way, that's as it should be. And yet, I'm more than halfway through at this point, and thus far A Memory of Light is as weak as Crossroads of Twilight turned out to be. . . :/

Enough with the filler, I want some killer material. . . Please. . . Pretty please!

Daniel Abraham's "When We Were Heroes" is a new Wild Cards short story available for free on Tor.com. According to the author, it's an original Wild Cards story about Marat/Sade, neoliberal colonialism, love, and superheroes. And it comes with a fabulous illustration by John Picacio!

Here's the blurb:

George R. R. Martin’s Wild Cards multi-author shared-world universe has been thrilling readers for over 25 years. Now, in addition to overseeing the ongoing publication of new Wild Cards books (like 2011’s Fort Freak), Martin is also commissioning and editing new Wild Cards stories for publication on Tor.com!

Daniel Abraham’s “When We Were Heroes” is an affecting examination of celebrity, privacy, and the different ways people deal with notoriety and fame—problems not made easier when what you’re famous for are superpowers that even you don’t fully understand.

Follow this link to read "When We Were Heroes."

I have three copies of Robert V. S. Redick's The Night of the Swarm up for grabs, compliments of the folks at Del Rey. For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe.

Here's the blurb:

Robert V. S. Redick brings his acclaimed fantasy series The Chathrand Voyage to a triumphant close that merits comparison to the work of such masters as George R. R. Martin, Philip Pullman, and J.R.R. Tolkien himself. The evil sorcerer Arunis is dead, yet the danger has not ended. For as he fell, beheaded by the young warrior-woman Thasha Isiq, Arunis summoned the Swarm of Night, a demonic entity that feasts on death and grows like a plague. If the Swarm is not destroyed, the world of Alifros will become a vast graveyard. Now Thasha and her comrades—the tarboy Pazel Pathkendle and the mysterious wizard Ramachni—begin a quest that seems all but impossible. Yet there is hope: One person has the power to stand against the Swarm: the great mage Erithusmé. Long thought dead, Erithusmé lives, buried deep in Thasha’s soul. But for the mage to live again, Thasha Isiq may have to die.

The rules are the same as usual. You need to send an email at reviews@(no-spam)gryphonwood.net with the header "SWARM." Remember to remove the "no spam" thingy.

Second, your email must contain your full mailing address (that's snail mail!), otherwise your message will be deleted.

Lastly, multiple entries will disqualify whoever sends them. And please include your screen name and the message boards that you frequent using it, if you do hang out on a particular MB.

Good luck to all the participants!

You can now pre-order John Scalzi's The B-Team for 0.99$ here.

Here's the blurb:

The opening episode of The Human Division, John Scalzi's new thirteen-episode novel in the world of his bestselling Old Man's War. Beginning on January 15, 2013, a new episode of The Human Division will appear in e-book form every Tuesday.

Colonial Union Ambassador Ode Abumwe and her team are used to life on the lower end of the diplomatic ladder. But when a high-profile diplomat goes missing, Abumwe and her team are last minute replacements on a mission critical to the Colonial Union’s future. As the team works to pull off their task, CDF Lieutenant Harry Wilson discovers there’s more to the story of the missing diplomats than anyone expected...a secret that could spell war for humanity.

At the publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied.

Fantasy and science fiction and speculative fiction book reviews, author interviews, bestseller news, contests and giveaways, etc. Enjoy!

Disclaimer:

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Join us on Facebook!!

Speculative Fiction Authors

- Joe Abercrombie

- Dan Abnett

- Daniel Abraham

- Saladin Ahmed

- Paolo Bacigalupi

- Iain M. Banks

- James Barclay

- Bradley P. Beaulieu

- Peter V. Brett

- Terry Brooks

- Tobias S. Buckell

- Jim Butcher

- Jacqueline Carey

- Blake Charlton

- David Constantine

- Stephen R. Donaldson

- Hal Duncan

- David Anthony Durham

- David Louis Edelman

- Steven Erikson

- S. L. Farrell

- Raymond E. Feist

- Jeffrey Ford

- C. S. Friedman

- Neil Gaiman

- William Gibson

- Peter F. Hamilton

- Tracy Hickman

- Robin Hobb

- Mark Hodder

- Charlie Huston

- J. V. Jones

- Guy Gavriel Kay

- Jasper Kent

- Kay Kenyon

- Stephen King

- Katherine Kurtz

- Mark Lawrence

- Sergey Lukyanenko

- Scott Lynch

- George R. R. Martin

- Robert McCammon

- Ian McDonald

- China Miéville

- L. E. Modesitt, jr.

- Michael Moorcock

- Richard Morgan

- Haruki Murakami

- Mark Charan Newton

- Naomi Novik

- Nnedi Okorafor

- K. J. Parker

- Tim Powers

- Terry Pratchett

- Melanie Rawn

- Alastair Reynolds

- Patrick Rothfuss

- Brian Ruckley

- Brandon Sanderson

- Courtney Schafer

- Ken Scholes

- Ekaterina Sedia

- Joel Shepherd

- Dan Simmons

- Melinda Snodgrass

- Jeff Somers

- Jon Sprunk

- Neal Stephenson

- Sam Sykes

- Adrian Tchaikovsky

- Ian Tregillis

- Carrie Vaughn

- Peter Watts

- Brent Weeks

- Margaret Weis

- David J. Williams

- Tad Williams

- Jack Whyte

- Chris Wooding

- Carlos Ruiz Zafón

Publishers

SFF Resources

Book trailer for Peter V. Brett's THE DAYLIGHT WAR

Publié par

Patrick

on Thursday, January 31, 2013

/

Comments: (1)

The folks at Harper Voyager UK just released this cool book trailer for Peter V. Brett's The Daylight War (Canada, USA, Europe).

Be My Enemy

Publié par

Patrick

on Wednesday, January 30, 2013

/

Comments: (2)

If you've been following this blog for a while, you are aware that I love Ian McDonald. To this day, River of Gods, Brasyl, and The Dervish House continue to rank among my favorite science fiction reads of all time. Hence, you can imagine my disappointment when it was announced that McDonald's next project would be aimed at the YA market.

Having said that, even though I gave Planesrunner a shot with a certain measure of reticence, the author's first YA work impressed me. Although the plot did not show as much depth and the storylines were not as multilayered and convoluted as is usually his wont, I found McDonald's Planesrunner to be an intelligent, entertaining, and fast-paced novel.

The sequel, Be My enemy, follows in the same vein. The book doesn't move the plot forward as much as the first installment did, but this second volume is another fun and entertaining novel which contains all the key ingredients that made Planesrunner such a good read!

Here's the blurb:

Everett Singh has escaped with the Infundibulum from the clutches of Charlotte Villiers and the Order, but at a terrible price. His father is missing, banished to one of the billions of parallel universes of the Panoply of All World, and Everett and the crew of the airship Everness have taken a wild, random Heisenberg Jump to a random parallel plane. Everett is smart and resourceful, and, from a frozen earth far beyond the Plenitude, he plans to rescue his family. But the villainous Charlotte Villiers is one step ahead of him.

The action traverses the frozen wastes of iceball earth; to Earth 4 (like ours, except that the alien Thryn Sentiency occupied the moon in 1964); to the dead London of the forbidden plane of Earth 1, where the emnants of humanity battle a terrifying nanotechnology run wild—and Everett faces terrible choices of morality and power. But Everett has the love and support of Sen, Captain Anastasia Sixsmyth, and the rest of the crew of Everness—as he learns that the deadliest enemy isn't the Order or the world-devouring nanotech Nahn—it's yourself.

It's no secret that the multiverse theory is an old science fiction trope. Some would say that parallel universes and parallel Earths have been done ad nauseam. That may be, but I found McDonald's approach, with such concepts as the Plenitude of Known Worlds and the Heisenberg Gates, to be relatively fresh. In Be My Enemy, the author explores a number of other realities. Given how Planesrunner ended, this second volume begins in a world trapped in ice and snow. In addition, the narrative takes readers to Earth 4, a world almost identical to our own but for mankind making contact with aliens in 1964. We also visit Earth 1, a forbidden plane of existence under quarantine where humanity has been brought on the brink of extinction by nanotechnology.

Though very fluid, McDonald's prose is evocative and every world and locale comes alive as you read along. I particularly enjoyed how arresting the imagery created by the author for the almost-dead world of Earth 1 turned out to be. The scenes taking place aboard the Everness are also special.

The coolest aspect of Be My Enemy remains McDonald's use of Everett's double from another plane of existence. That was absolutely brilliant and it opened up so many possibilities. Another Everett who knows virtually everything his counterpart does, but enhanced with alien Thryn technology, this teenager is forced by Charlotte Villiers to go after Everett Singh and the secrets he carries. But what the Plenipotentiaries failed to grasp is that this other Everett also has plans of his own.

Once more, the characterization is top notch. McDonald came up with an endearing and disparate cast of protagonists for Planesrunner and most of them are back in this second installment. Everett Singh must share the spotlight with his double from Earth 4 and there is a nice balance between the two POVs. The crew of the airship Everness makes for a compelling supporting cast, and it was a pleasure to see Captain Anastasia Sixsmyth, the mysterious Sen, the God-fearing Mr.Sharkey, and the grumbling Mchynlyth again.

As was the case with its predecessor, the pace is fast and crisp throughout Be My Enemy. So much so that you go through this slim (269 pages) book in no time. As I mentioned earlier, this volume focuses more on the confrontation between Everett Singh and Everett M than anything else, which means that the storylines don't progress as much as I would have thought. Still, the way the author brought Be My Enemy to a close opens the door for plenty of awesome things to come, in a number of different realities. Lou Anders told me that volume 3 should, if all goes well, see the light in the winter of 2014.

All in all, Be My Enemy may not be akin to the mind-blowing science fiction yarns Ian McDonald is renowned for. And yet, like Planesrunner, it's a fun, entertaining, more and more complex work featuring an engaging cast of characters. If like me, you have a bias against YA books, McDonald's Everness series should win you over. Writing for a younger audience imbues McDonald's writing with a certain exuberance that I found intoxicating.

Give these books a shot! Planesrunner and Be My Enemy won't disappoint!

The final verdict: 7.75/10

For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe

Miles Cameron contest winner!

Publié par

Patrick

/

Comments: (0)

This lucky winner will get her hands on an ARC of Miles Cameron's The Red Knight. For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe.

The winner is:

- Anja Neumann, from Heidelberg, Germany

Many thanks to all the participants!

The winner is:

- Anja Neumann, from Heidelberg, Germany

Many thanks to all the participants!

More inexpensive ebook goodies!

Publié par

Patrick

/

Comments: (1)

You can now download John Scalzi's third episode in The Human Division series, We Only Need the Heads, for 0.99$ here.

Here's the blurb:

The third episode of The Human Division, John Scalzi's new thirteen-episode novel in the world of his bestselling Old Man's War. Beginning on January 15, 2013, a new episode of The Human Division will appear in e-book form every Tuesday.

CDF Lieutenant Harry Wilson has been loaned out to a CDF platoon tasked with secretly removing an unauthorized colony of humans on an alien world. Colonial Ambassador Abumwe has been ordered to participate in final negotiations with an alien race the Union hopes to make allies. Wilson and Abumwe’s missions are fated to cross—and in doing so, place both missions at risk of failure.

At the publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied.

Win a copy of George R. R. Martin's TUF VOYAGING

Publié par

Patrick

on Monday, January 28, 2013

/

Comments: (6)

Bantam Books have re-issued George R. R. Martin's Tuf Voyaging in trade paperback format and I'm giving away a copy to one lucky winner! For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe.

Here's the blurb:

Long before A Game of Thrones became an international phenomenon, #1 New York Times bestselling author George R. R. Martin had taken his loyal readers across the cosmos. Now back in print after almost ten years, Tuf Voyaging is the story of quirky and endearing Haviland Tuf, an unlikely hero just trying to do right by the galaxy, one planet at a time.

Haviland Tuf is an honest space-trader who likes cats. So how is it that, in competition with the worst villains the universe has to offer, he’s become the proud owner of a seedship, the last remnant of Earth’s legendary Ecological Engineering Corps? Never mind; just be thankful that the most powerful weapon in human space is in good hands—hands which now have the godlike ability to control the genetic material of thousands of outlandish creatures.

Armed with this unique equipment, Tuf is set to tackle the problems that human settlers have created in colonizing far-flung worlds: hosts of hostile monsters, a population hooked on procreation, a dictator who unleashes plagues to get his own way . . . and in every case, the only thing that stands between the colonists and disaster is Tuf’s ingenuity—and his reputation as a man of integrity in a universe of rogues.

The rules are the same as usual. You need to send an email at reviews@(no-spam)gryphonwood.net with the header "TUF." Remember to remove the "no spam" thingy.

Second, your email must contain your full mailing address (that's snail mail!), otherwise your message will be deleted.

Lastly, multiple entries will disqualify whoever sends them. And please include your screen name and the message boards that you frequent using it, if you do hang out on a particular MB.

Good luck to all the participants!

Yes, it's crazy cold in Montréal. . .

Publié par

Patrick

/

Comments: (0)

But we still know how to have a good time!! ;-)

Calling on all self-published/indie speculative fiction writers

Publié par

Patrick

on Sunday, January 27, 2013

/

Comments: (163)

Indie authors. . .

It does have a nicer ring to it, I agree. . . But it doesn't change the fact that it's synonymous with "self-published writers." You can sugarcoat it any way you like, it means that you published something through a vanity press or something similar. You can call a woman an administrative assistant, but she's still a secretary. One might prefer to be called an adult entertainment performer, yet he or she remains a pornstar. Ask anyone working at The Home Depot or Walmart if they're proud to be an associate instead of an employee and they'll give you the finger.

So indie author or self-published writer amounts to the exact same thing. Like many SFF online reviewers, I refuse to read any self-published work. There is enough crap out there that nevertheless went through the normal publishing process that I have no time to waste on something that wasn't good enough to attract the attention of an agent and then go through the usual editing process.

For the last year or two, these so-called indie authors have become more and more vocal on various SFF message boards and other online communities, bemoaning the fact that it's very difficult for them to get the word out about their novels/series. They often point the finger at reviewers like me, people who refuse to give self-published books a shot. They are quick to point out the very few exceptions that "made it," refusing to agree with the fact that most of the stuff that ever came out of vanity presses has always been worthless crap.

Hence, even though I'm one of those readers who believe that 99% of indie works are literary turds, I'm willing to give those authors a chance to put their money where their mouths are. So here's the deal:

In the comment section of this post, I'll give indie authors the opportunity to make their sale's pitch. Provide the title of your novel and a blurb that will give us an idea of what the book is all about. In addition, I want you to tell me why you believe I'd enjoy it. I'll let this run its course for a while, and then I'll select the five works whose premise intrigued me enough to give them a shot.

That done, I will ask my readers to vote on which work they would like me to read and perhaps review. Once the votes are tallied, I will officially commit to read the first 100 pages of the book the Hotlist readers will have voted for. If it's decent, I will read the whole thing and review it on the Hotlist. If it's good, I will humbly admit that I was wrong and that perhaps reviewers should give more self-published works a shot.

The catch: If it sucks, I will show NO MERCY. So before making your sale's pitch, make sure you understand this. I have books from quality authors such as Neil Gaiman, Richard Morgan, Neal Stephenson, George R. R. Martin, Stephen King, Iain M. Banks, China Miéville, Alastair Reynolds, yada yada yada, waiting to be read. If you make me waste my time on total crap, I will make you feel as though I've been going easy on Robert Stanek and Terry Goodkind these last few years. I kid you not. I won't hold anything back.

Please don't make me regret this. . . :/

The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince

Publié par

Patrick

/

Comments: (2)

As a huge fan of Robin Hobb and her Six Duchies novels, I was thrilled when it was announced that she was writing a novella which would focus on the Farseer line's magical power. With The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince, the author would finally reveal how the Farseer family acquired their mysterious powers. I was quite intrigued, to say the least!

Here's the blurb:

One of the darkest legends in the Realm of the Elderlings recounts the tale of the so-called Piebald Prince, a Witted pretender to the throne unseated by the actions of brave nobles so that the Farseer line could continue untainted. Now the truth behind the story is revealed through the account of Felicity, a low-born companion of the Princess Caution at Buckkeep.

With Felicity by her side, Caution grows into a headstrong Queen-in-Waiting. But when Caution gives birth to a bastard son who shares the piebald markings of his father’s horse, Felicity is the one who raises him. And as the prince comes to power, political intrigue sparks dangerous whispers about the Wit that will change the kingdom forever…

Internationally-bestselling, critically-acclaimed author Robin Hobb takes readers deep into the history behind the Farseer series in this exclusive, new novella, “The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince.” In her trademark style, Hobb offers a revealing exploration of a family secret still reverberating generations later when assassin FitzChivalry Farseer comes onto the scene. Fans will not want to miss these tantalizing new insights into a much-beloved world and its unforgettable characters.

The novella is split into two parts, "The Willful Princess" and "The Piebald Prince." The first one focuses on Princess Caution Farseer, willful daughter of King Virile and Queen Capable. It chronicles the events of her life, from her name-sealing day until the day she gave birth to her only child. From the beginning, Caution is a spoiled brat who'll become an annoying teenager, and then a capricious Queen-in-Waiting.

The tale is told by Felicity, daughter of Princess Caution's wet-nurse. Although low-born, Felicity will become Caution's best friend, confidante, and lover. Trouble is, Felicity isn't a very interesting or even likeable POV protagonist. And since the entire novella unfolds through her eyes, that creates a problem. I understand that for the secrets to go down through the subsequent Farseer generations, it needed to be recorded by a third party. Hence, Felicity and Redbird's importance cannot be put into question. It's just that Felicity isn't an engaging narrator. And given how critical and fascinating the truth behind the Farseer's mysterious magical powers will be in the two series featuring the beloved character FitzChivalry, I believe the tale would have been better had it featured POVs by Princess Caution, Lostler, Lord Canny, Lady Wiffen, and King Charger.

I feel it would have given more depth to the story. As things stand, with everything being recounted by Felicity, the novella lacks the usual emotional punch that characterize basically all of Robin Hobb's tales.

Beyond the secrets behind the Farseer line's mystical powers, I enjoyed how The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince also elaborated on why the Wit became so feared and Witted People became persecuted all over the Six Duchies.

Although Hobb's storylines are as absorbing as is habitually her wont, I found that Felicity's narrative could be a bit off-putting at times. The pace can drag a bit in certain portions of the first part. Yet the rhythm is perfect in "The Piebald Prince."

Regardless of its shortcomings, I found The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince to be a worthy addition to the Six Duchies' canon. Can't wait to read another novel/series featuring FitzChavalry again!!

The final verdict: 7.25/10

For more info about this title, check out the Subterranean Press website.

Extract from Robert V. S. Redick's THE NIGHT OF THE SWARM

Publié par

Patrick

/

Comments: (0)

Thanks to the folks at Del Rey, here's an excerpt from Robert V. S. Redick's The Night of the Swarm. For more info about this title: Canada, USA, Europe.

Here's the blurb:

Robert V. S. Redick brings his acclaimed fantasy series The Chathrand Voyage to a triumphant close that merits comparison to the work of such masters as George R. R. Martin, Philip Pullman, and J.R.R. Tolkien himself. The evil sorcerer Arunis is dead, yet the danger has not ended. For as he fell, beheaded by the young warrior-woman Thasha Isiq, Arunis summoned the Swarm of Night, a demonic entity that feasts on death and grows like a plague. If the Swarm is not destroyed, the world of Alifros will become a vast graveyard. Now Thasha and her comrades—the tarboy Pazel Pathkendle and the mysterious wizard Ramachni—begin a quest that seems all but impossible. Yet there is hope: One person has the power to stand against the Swarm: the great mage Erithusmé. Long thought dead, Erithusmé lives, buried deep in Thasha’s soul. But for the mage to live again, Thasha Isiq may have to die.

Enjoy!

-----------------------

Author’s Note: the setting of this chapter is the ancient sailing ship Chathrand, Captain Nilus Rose commanding, as it flees the hostile waters of the empire of Bali Adro. There are quite a few actors on stage (on deck) but I think readers will be able to follow the dynamics of the scene without knowing all the personalities involved.

From the Final Journal of G. Starling Fiffengurt, Quartermaster

Wednesday, 20 Halar 942. The wolves have finally pounced.

As I write this, I feel how lucky we are to be alive. Whether luck & life will still be with us much longer is uncertain. For now all credit goes to Captain Rose. People change; ships grow faster, arms more diabolical. But nothing beats a seasoned skipper, no matter his moods or eccentricities.

Five bells. Lunch still heavy in my stomach. A shout from the crow’s nest: Ship dead astern! I happened to be right there at the wheel with Elkstem, and we rushed to the spankermast speaking-tube to hear the man properly.

“She was hid by the island, it’s not my fault!” he shouts. That told us next to nothing: there were islands all about us: great and small, settled and unsettled (though with each day north we saw fewer signs of habitation), sandy and stony, lush and bone-dry. We’d been winding among them for a week.

“A monster of a boat!” the lookout’s shouting. “Ugly, huge! She’s five times our measure if she’s a yard.”

“Five times our blary length?” cries the sailmaster. “Gather your wits, man, that’s impossible! Distance! Heading!”

“Maybe longer, Mr. Elkstem! I can’t be sure; she’s forty miles astern. And Rin slay me if she don’t have a halo of fire above her. Devil-fire, I mean! Something foul beyond foul.”

“What heading is she on, damn you?” I bellow.

“East, Mr. Fiffengurt, or east-by-southeast. They’re under full sail, sir, and—”

Silence. We both scream at the poor lad, and then he answers shrilly: “Correction, correction! Vessel tacking northward! They’ve spied us!”

Not just spied, but fingered us for dinner, it appeared. I blew the whistle; the lieutenants started bellowing like hounds; in seconds we were preparing for war.

From the hatches men spilled like ants, the dlömu answering the call as quickly as the humans, if not more so. Mr. Leef finally brought me a telescope. I raised it, but shut my eyes before I looked. No fear, no fear, the lads’ eyes are upon you.

The vessel was a horror. It was a Plazic invention to be sure, one of the foul things sustained by the magic the dlömu had drawn from the bones of the lizard-demons called eguar. Prince Olik had told us a little, and the dlömic sailors a little more. Eguar-magic was the power behind the Bali Adro throne, & its doom. It had made her armies invincible—and made their commanders depraved and self-destroying. It is a frightful state of affairs, and one that reminds me uncomfortably of our own dear Empire across the sea.

We’d seen monster-vessels before, in the terrible Armada that passed so close to us just after we reached the Southern main. But this was something else altogether. Impossibly large and shapeless, it was like a giant, shabby fortress or cluster of warehouses that had somehow gone to sea. How did it move? There were sails, but they were preposterous: ribbed things that jutted out like the fins of a spiny rockfish. It should have been dead in the water, but the blue gap between it & the island was growing. It was under way.

Captain Rose bounded up the Silver Stair. Without a glance at me he climbed the quarterdeck ladder, and kept going to the mizzen yard, where he trained his own scope on the vessel. He held still a long time (what’s a long time when your heart’s in your throat?) as Elkstem and I gazed up at him. When he turned to us, his look was sober and direct.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “you are distinguished seamen: use your skills. This foe we cannot fight. We must elude it until nightfall or we shall lose the Chathrand.”

The captain’s rages are frightful, but his compliments simply terrify: he saves them for the worst of moments. He hung there, face unreadable within that red beard, one elbow hitched around a backstay. He examined the skies: blue above us, thick clouds to windward. Islands on all sides, of course. Rose looked over each of them in turn.

His eyes narrowed suddenly. He pointed at a dark, mountainous island, some forty miles off the starboard bow. “That one. What is it called?”

Elkstem told him that it was Phyreis, one of the last charted islands in the Wilderness. “And a big one, Captain. Half the size of Bramian, maybe,” he said.

“It appears to sharpen to a point.”

“The chart attests to it, sir: a long southwest headland.”

Rose nodded. “Listen well, then. We must be fifteen miles off that point at nightfall. That will be at seven bells plus twenty minutes. Until then we are to stay as far as possible ahead of the enemy, without ever allowing him to cut us off from Phyreis. Is that perfectly clear?”

“By nightfall—” I began.

“Fiffengurt.” He cut me off, suddenly wrathful. “You have just disgraced your very uniform. Did I say by nightfall? No, Quartermaster: my command was at nightfall. Earlier is unacceptable, later equally so. If these orders are beyond your comprehension I will appoint someone fit to carry them out.”

“Oppo, sir,” I said hastily. “At nightfall, fifteen miles off the point.”

Rose nodded, his eyes still on me. “The precise course I leave to your combined discretion. The canvas likewise. That is all.”